LinkedIn: Why Success Posts Can Hurt More Than Help

I’m a heavy LinkedIn user, and this weekend, I got caught red-handed in the act of toxic comparison.

Understand

4 déc. 2025

7 min

A wave of anxiety hit after seeing three posts in a row from entrepreneurs showcasing spectacular success. And I kept scrolling.Often overlooked in the category of addictive social networks, LinkedIn has plenty of reasons to be taken seriously. Just like any other platform, it can affect both our productivity and our mental health.

A Brief History of LinkedIn

LinkedIn was founded in 2003 by Reid Hoffman and Allen Blue, in California.

Since then, a few key milestones:

2006: Hit 5 million members

2008: Launched in France and opened a London office

2011: Went public and reached 100 million users

2016: Acquired by Microsoft for $27 billion (yes, LinkedIn is part of the GAFAM now…)

2017: Reached 500 million members

2021: Hit $10 billion in revenue

2023: 1 billion members (!)

As of early 2024, France ranks 5th globally in terms of LinkedIn users, with 29 million members. I suspect you’re one of them. First, let me say I really like LinkedIn for a lot of things. It’s incredibly effective for:

connecting with other professionals

staying informed about trends in your field

following thought leaders

exploring career opportunities

showcasing your work or contributions

It’s the go-to platform for our professional lives. I’ve been posting on LinkedIn for six months now, and even so, I’ve noticed some harmful tendencies that come from using it the wrong way.

The Comparison Trap

“Comparison is the thief of joy.” — Seneca

Originally, comparison was a survival mechanism. It helped us learn and adapt—a vital skill for our ancestors. We evolved by becoming sensitive and attuned to what others thought and felt about us. Belonging to a group meant being aware of hierarchies and social status. In short, we’ve always tried to define ourselves in relation to others: different or similar, better or worse. This trait, hardwired into our DNA, has taken on a whole new dimension in the 21st century.

Thanks to digital technology, we now have unlimited, 24/7 access to what everyone else is doing. To cut to the chase, a 2019 article from Slate provocatively stated:

“If the rest of social media is where we go to see that everyone’s having more fun than us, LinkedIn is where we go to see that everyone is more successful than us.”

Back in 1954, American psychologist Leon Festinger theorized how people compare themselves to others. There are three directions:

Lateral comparison: with people who are similar to us

Downward comparison: with those who have less than we do

Upward comparison: with those who have more

It’s often a double-edged sword. An upward comparison can fuel healthy ambition, give us energy, and lift us higher. It can also stir jealousy, dissatisfaction, and anxiety. A downward comparison can trigger gratitude for what we have. It can also provoke disdain or contempt. The issue isn’t comparison itself—it’s how mindlessly we do it. It requires discernment.

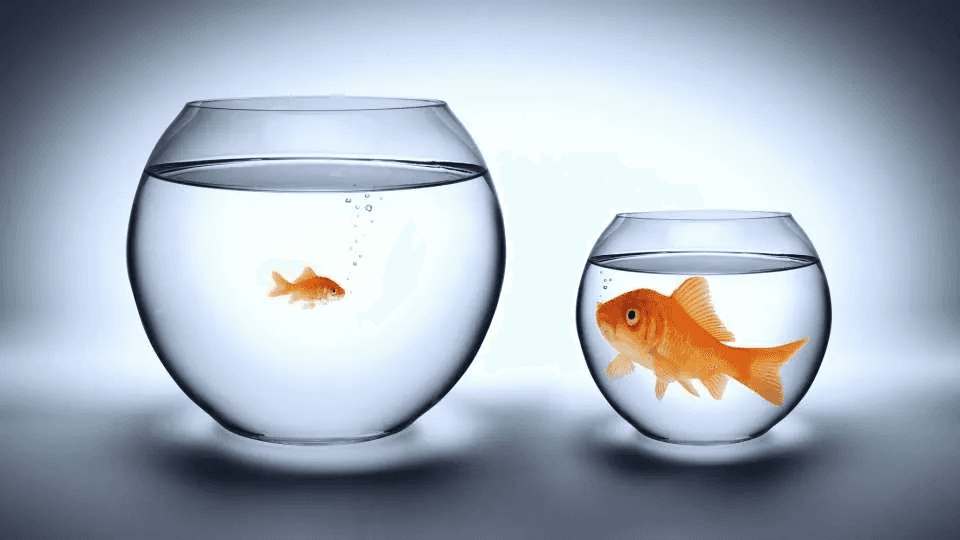

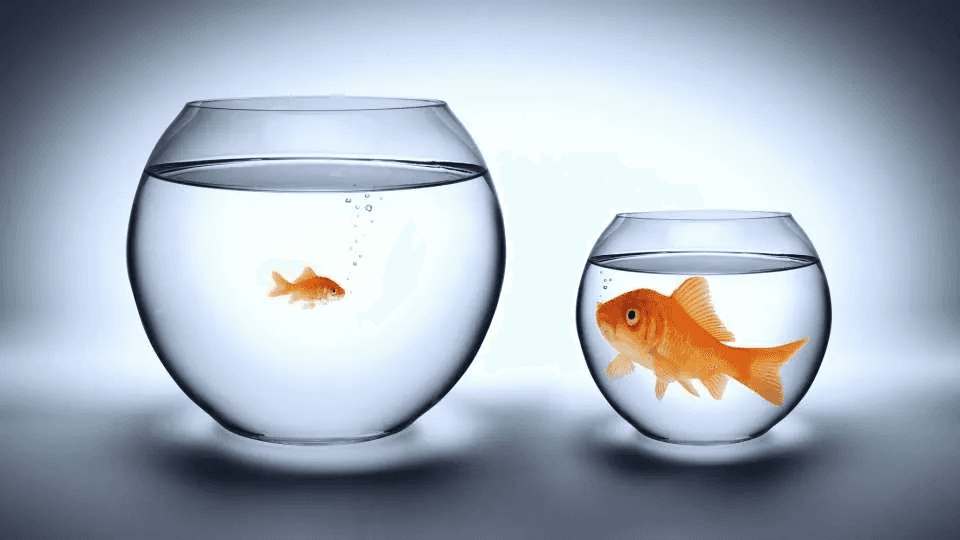

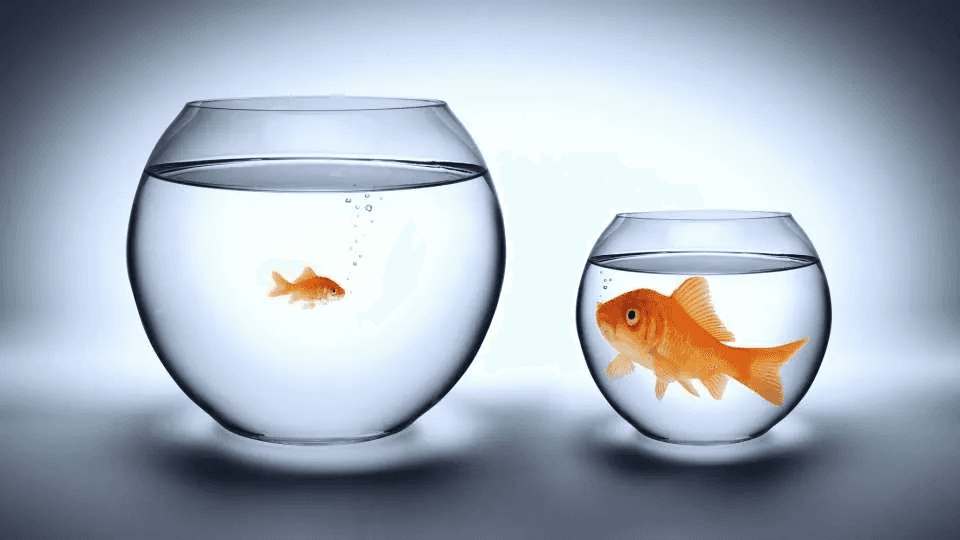

In chess, a rook is powerful compared to a pawn—but not against a queen. Likewise, a fish may feel huge in a small pond but tiny in the vast ocean.

LinkedIn fuels this urge to compare through a whole arsenal: your profile, number of connections, job title, promotions, likes, profile views… Comparison happens not just with people we know—but also those we don’t. Naturally, as we measure ourselves against others, we start drawing hasty conclusions about our own careers and accomplishments.

A wave of anxiety hit after seeing three posts in a row from entrepreneurs showcasing spectacular success. And I kept scrolling.Often overlooked in the category of addictive social networks, LinkedIn has plenty of reasons to be taken seriously. Just like any other platform, it can affect both our productivity and our mental health.

A Brief History of LinkedIn

LinkedIn was founded in 2003 by Reid Hoffman and Allen Blue, in California.

Since then, a few key milestones:

2006: Hit 5 million members

2008: Launched in France and opened a London office

2011: Went public and reached 100 million users

2016: Acquired by Microsoft for $27 billion (yes, LinkedIn is part of the GAFAM now…)

2017: Reached 500 million members

2021: Hit $10 billion in revenue

2023: 1 billion members (!)

As of early 2024, France ranks 5th globally in terms of LinkedIn users, with 29 million members. I suspect you’re one of them. First, let me say I really like LinkedIn for a lot of things. It’s incredibly effective for:

connecting with other professionals

staying informed about trends in your field

following thought leaders

exploring career opportunities

showcasing your work or contributions

It’s the go-to platform for our professional lives. I’ve been posting on LinkedIn for six months now, and even so, I’ve noticed some harmful tendencies that come from using it the wrong way.

The Comparison Trap

“Comparison is the thief of joy.” — Seneca

Originally, comparison was a survival mechanism. It helped us learn and adapt—a vital skill for our ancestors. We evolved by becoming sensitive and attuned to what others thought and felt about us. Belonging to a group meant being aware of hierarchies and social status. In short, we’ve always tried to define ourselves in relation to others: different or similar, better or worse. This trait, hardwired into our DNA, has taken on a whole new dimension in the 21st century.

Thanks to digital technology, we now have unlimited, 24/7 access to what everyone else is doing. To cut to the chase, a 2019 article from Slate provocatively stated:

“If the rest of social media is where we go to see that everyone’s having more fun than us, LinkedIn is where we go to see that everyone is more successful than us.”

Back in 1954, American psychologist Leon Festinger theorized how people compare themselves to others. There are three directions:

Lateral comparison: with people who are similar to us

Downward comparison: with those who have less than we do

Upward comparison: with those who have more

It’s often a double-edged sword. An upward comparison can fuel healthy ambition, give us energy, and lift us higher. It can also stir jealousy, dissatisfaction, and anxiety. A downward comparison can trigger gratitude for what we have. It can also provoke disdain or contempt. The issue isn’t comparison itself—it’s how mindlessly we do it. It requires discernment.

In chess, a rook is powerful compared to a pawn—but not against a queen. Likewise, a fish may feel huge in a small pond but tiny in the vast ocean.

LinkedIn fuels this urge to compare through a whole arsenal: your profile, number of connections, job title, promotions, likes, profile views… Comparison happens not just with people we know—but also those we don’t. Naturally, as we measure ourselves against others, we start drawing hasty conclusions about our own careers and accomplishments.

A wave of anxiety hit after seeing three posts in a row from entrepreneurs showcasing spectacular success. And I kept scrolling.Often overlooked in the category of addictive social networks, LinkedIn has plenty of reasons to be taken seriously. Just like any other platform, it can affect both our productivity and our mental health.

A Brief History of LinkedIn

LinkedIn was founded in 2003 by Reid Hoffman and Allen Blue, in California.

Since then, a few key milestones:

2006: Hit 5 million members

2008: Launched in France and opened a London office

2011: Went public and reached 100 million users

2016: Acquired by Microsoft for $27 billion (yes, LinkedIn is part of the GAFAM now…)

2017: Reached 500 million members

2021: Hit $10 billion in revenue

2023: 1 billion members (!)

As of early 2024, France ranks 5th globally in terms of LinkedIn users, with 29 million members. I suspect you’re one of them. First, let me say I really like LinkedIn for a lot of things. It’s incredibly effective for:

connecting with other professionals

staying informed about trends in your field

following thought leaders

exploring career opportunities

showcasing your work or contributions

It’s the go-to platform for our professional lives. I’ve been posting on LinkedIn for six months now, and even so, I’ve noticed some harmful tendencies that come from using it the wrong way.

The Comparison Trap

“Comparison is the thief of joy.” — Seneca

Originally, comparison was a survival mechanism. It helped us learn and adapt—a vital skill for our ancestors. We evolved by becoming sensitive and attuned to what others thought and felt about us. Belonging to a group meant being aware of hierarchies and social status. In short, we’ve always tried to define ourselves in relation to others: different or similar, better or worse. This trait, hardwired into our DNA, has taken on a whole new dimension in the 21st century.

Thanks to digital technology, we now have unlimited, 24/7 access to what everyone else is doing. To cut to the chase, a 2019 article from Slate provocatively stated:

“If the rest of social media is where we go to see that everyone’s having more fun than us, LinkedIn is where we go to see that everyone is more successful than us.”

Back in 1954, American psychologist Leon Festinger theorized how people compare themselves to others. There are three directions:

Lateral comparison: with people who are similar to us

Downward comparison: with those who have less than we do

Upward comparison: with those who have more

It’s often a double-edged sword. An upward comparison can fuel healthy ambition, give us energy, and lift us higher. It can also stir jealousy, dissatisfaction, and anxiety. A downward comparison can trigger gratitude for what we have. It can also provoke disdain or contempt. The issue isn’t comparison itself—it’s how mindlessly we do it. It requires discernment.

In chess, a rook is powerful compared to a pawn—but not against a queen. Likewise, a fish may feel huge in a small pond but tiny in the vast ocean.

LinkedIn fuels this urge to compare through a whole arsenal: your profile, number of connections, job title, promotions, likes, profile views… Comparison happens not just with people we know—but also those we don’t. Naturally, as we measure ourselves against others, we start drawing hasty conclusions about our own careers and accomplishments.

Votre téléphone, vos règles. Bloquez ce que vous voulez, quand vous voulez.

Pour 30 minutes

Tous les jours

Le week-end

Pendant les heures de travail

De 22h à 8h

Pour 7 jours

Tout le temps

Votre téléphone, vos règles. Bloquez ce que vous voulez, quand vous voulez.

Pour 30 minutes

Tous les jours

Le week-end

Pendant les heures de travail

De 22h à 8h

Pour 7 jours

Tout le temps

Votre téléphone, vos règles. Bloquez ce que vous voulez, quand vous voulez.

Pour 30 minutes

Tous les jours

Le week-end

Pendant les heures de travail

De 22h à 8h

Pour 7 jours

Tout le temps

The Dark Side

The irresistible need for social comparison can lead to compulsive behavior.

A distraction

That need—paired with infinite scroll—makes for a powerful time trap. The classic “just one minute” often becomes 20 or 30. Time you instantly regret. It’s hard to stop scrolling.

This is the intermittent reward principle, like a slot machine: even if only 1 in 10 posts interests us or sparks emotion, it’s the anticipation that keeps us hooked.

LinkedIn has become a quick and easy distraction: instead of focusing on your tasks, you check what others are up to. Low effort + comparison = a winning combo for the brain. And of course, once you’re on the platform, LinkedIn wants to keep you there. Proof: any external link in a post automatically reduces its reach (yes, it’s annoying for me too). Every notification, like, or profile view gives you a little dopamine hit. Which trains your brain to repeat the behavior: “Let’s check LinkedIn to see if there’s something new.”

Lower self-esteem and anxiety

It goes further than that. Habitually checking LinkedIn can intensify that nagging pressure of “Am I enough?”—a byproduct of repeated upward comparisons.

It’s the social network of winning. Every session, you’re bombarded with images of success and achievement. Watching from the sidelines can cause stress and anxiety—especially when it makes us feel uncertain. But comparison is also a defense mechanism against uncertainty—particularly when we’re feeling vulnerable. So it becomes a vicious cycle 🔄 …The more we compare, the more uncertain we feel. The more uncertain we are, the more we compare.

LinkedIn is a distorted mirror. We base our judgments on incomplete information. We take a single fact and draw conclusions about an entire person—their success, their happiness—and then compare all that to ourselves.

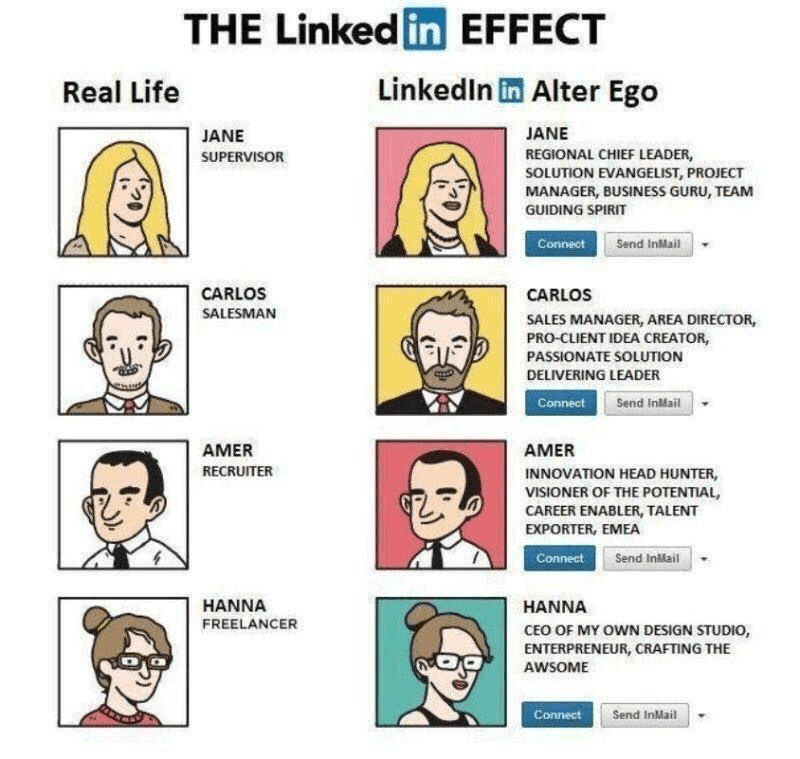

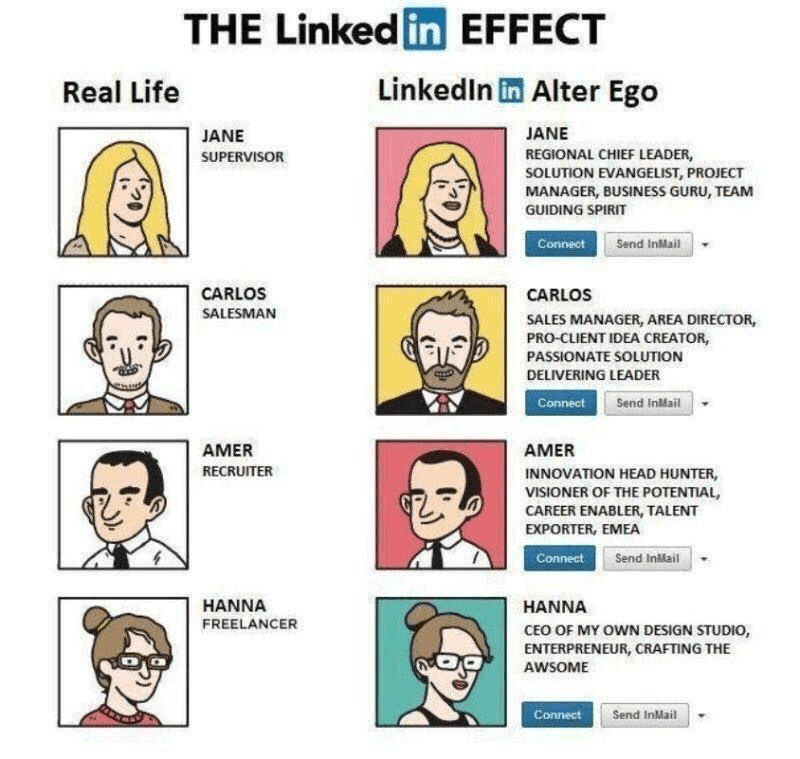

The truth is usually much more nuanced. The trap, like on all social platforms, is that we compare our inner world—our flaws—to the outer image others choose to show. This gap deepens the feeling of uncertainty. Social comparison also pushes people to self-promote on LinkedIn. And the platform becomes a masquerade.

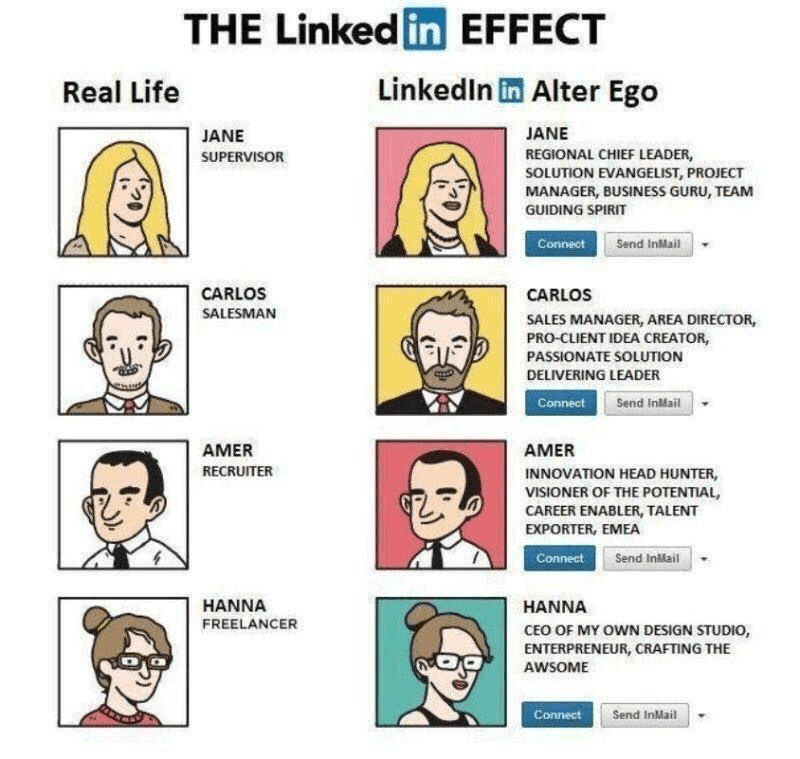

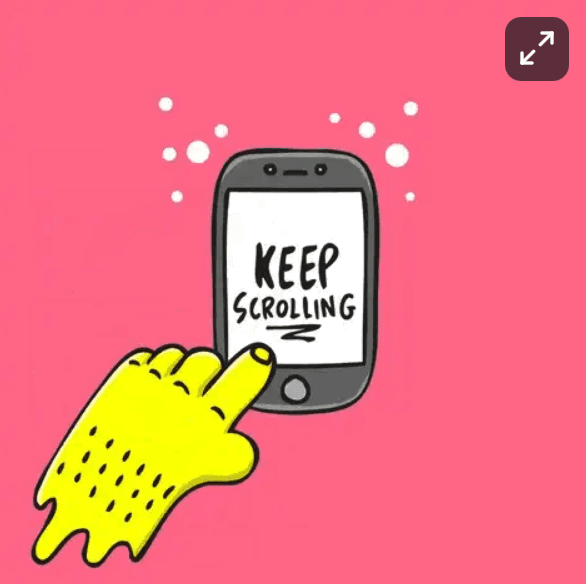

The Great Theatre

American sociologist Erving Goffman came up with the theory of self-presentation—the strategies we use to shape how others see us. It’s all about making a good impression.

According to him, the social world is a stage, structured by norms, values, and desirable goals. We unconsciously view life as a performance, where we’re constantly playing a role. It’s all about presenting yourself as respectable and trustworthy. LinkedIn is no exception. Everyone plays their part—creators and consumers alike. As a consumer, we only interact with what we’re comfortable letting others (boss, friends, whoever) see. So we don’t always engage with what truly interests us. It’s the quest for social validation: approval and recognition from others becomes the goal.

As a creator, I really struggled at first. My early posts on LinkedIn were a major source of stress. To be honest, I was scared of looking like an idiot. More generally, that’s the issue with LinkedIn: out of fear of ridicule or backlash, people often share content that’s bland, flawless, and sometimes uninteresting.

Every user, wanting to keep a polished image, presents themselves a certain way. This uniformity hides the diversity of real experiences—making comparisons and inspirations less authentic, and therefore less valuable. The true essence of our stories and thoughts remains backstage. That’s why I appreciate the build in public trend—and I plan to do more of it.

Epictetus and Yesterday’s Self

Repetitive comparison and the hunt for validation can sometimes be motivating—but often, they’re a detour. We highlight what we lack, instead of building on what we have. And that makes us lose sight of what truly matters. The Stoic philosopher Epictetus once said:

“The greatness of the soul lies not in being superior to others, but in being superior to your former self.”

Yes, I know—it sounds a bit like a cheap motivational quote. But I truly believe it can inspire us. It’s an invitation to focus on our own progress. Even if the grass seems greener elsewhere, let’s tend to our own lawn.

On LinkedIn, that mindset becomes especially crucial. The platform constantly invites us to measure our journey against others—without context, without background, without considering the effort involved. We might find ourselves up against a level 80 Pokémon while we’re still at level 5. And we forget to put that duel into perspective. If we must compare, let’s at least do it thoughtfully—not impulsively. That’s why I’ve added friction to my LinkedIn use—because I know how the platform can make me feel.

The Trick

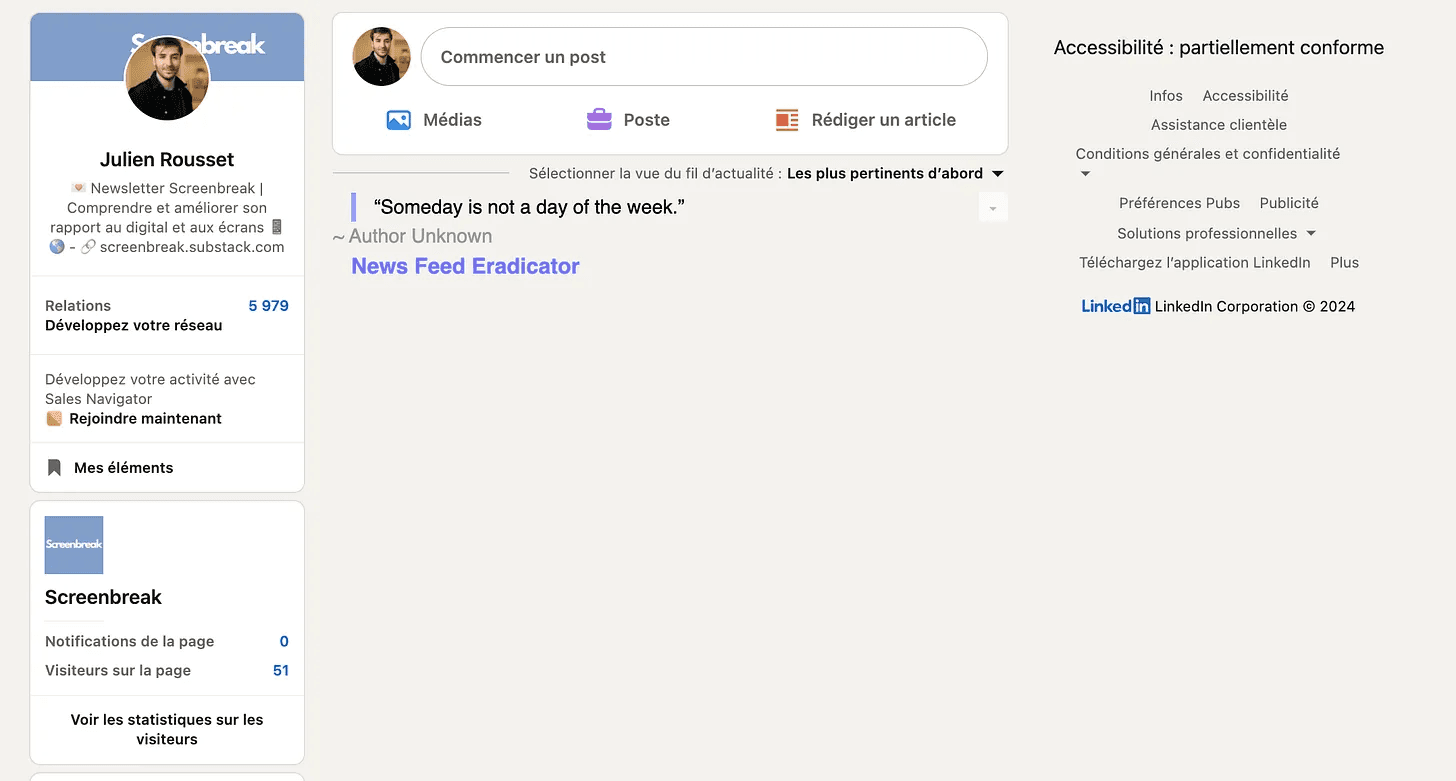

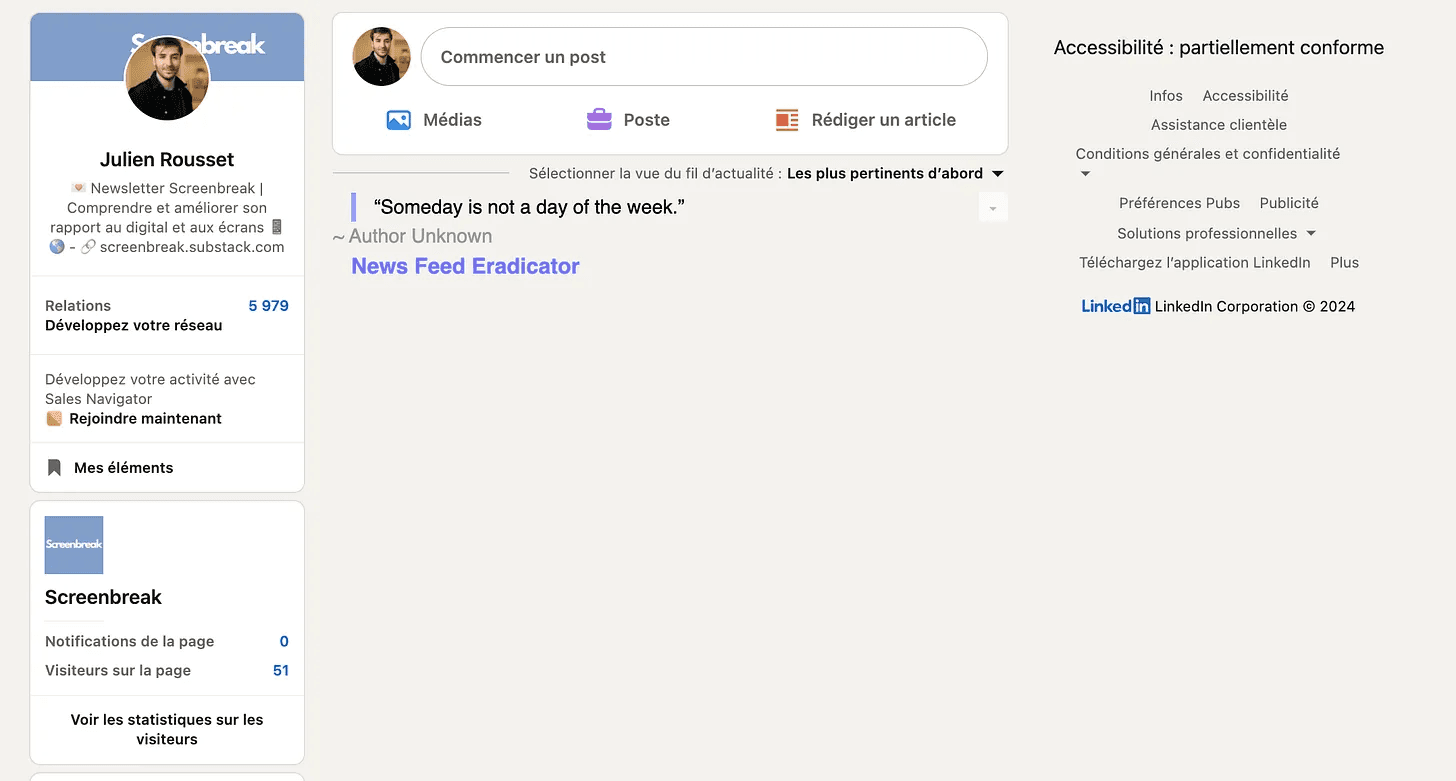

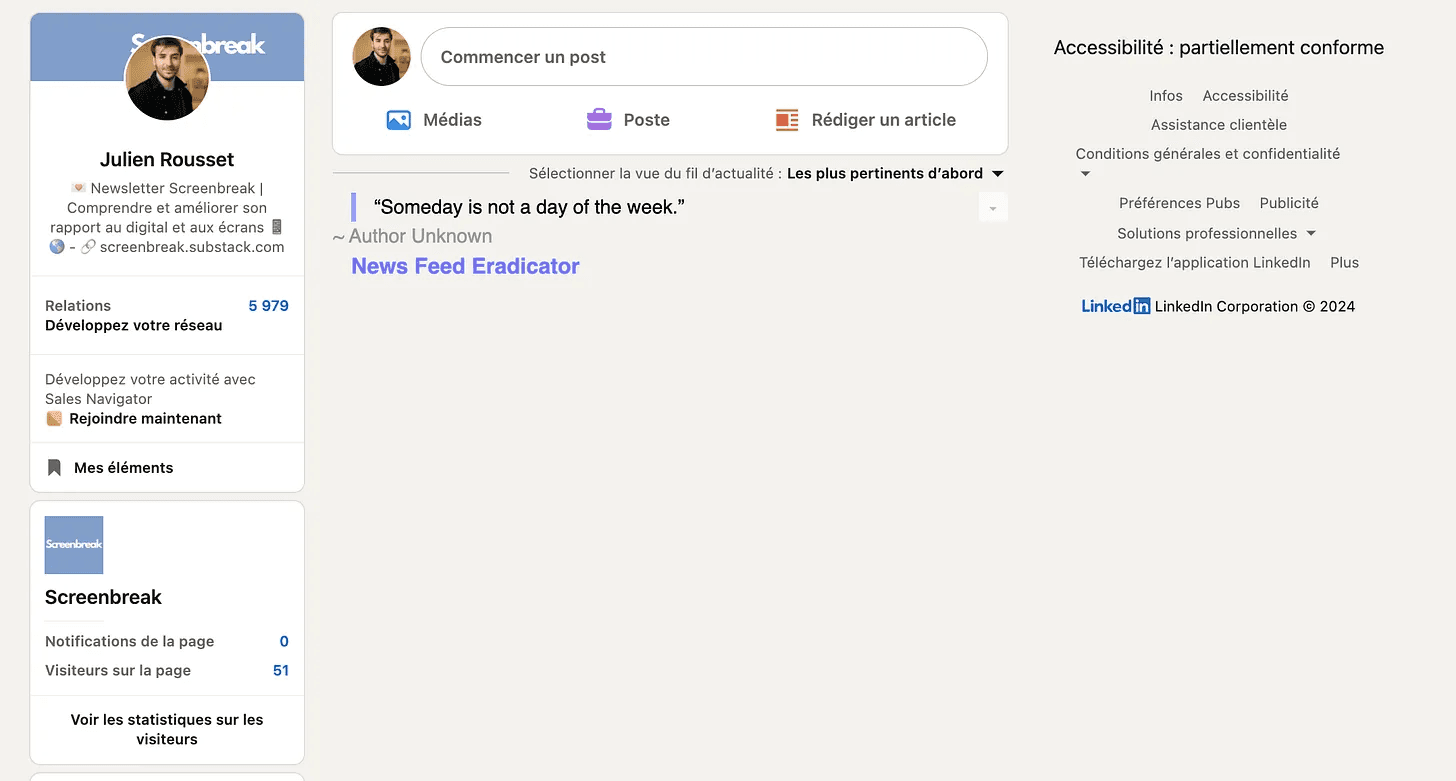

Even before I started writing content on LinkedIn, I was already spending a lot of time there. It kept growing. A few months ago, I installed the News Feed Eradicator extension—and I never looked back. Basically, it replaces your news feed with an inspirational quote.

I use it 95% of the time—even when I want to post or reply to messages. It lets me do what I came for without falling into the infinite scroll trap. It’s also a helpful reminder—“oh right, I don’t even know why I opened this”—when I land on LinkedIn out of habit. Once or twice a day, I’ll intentionally disable the extension for a few minutes to check in on what’s happening in my network—trying to stay an active, intentional user.

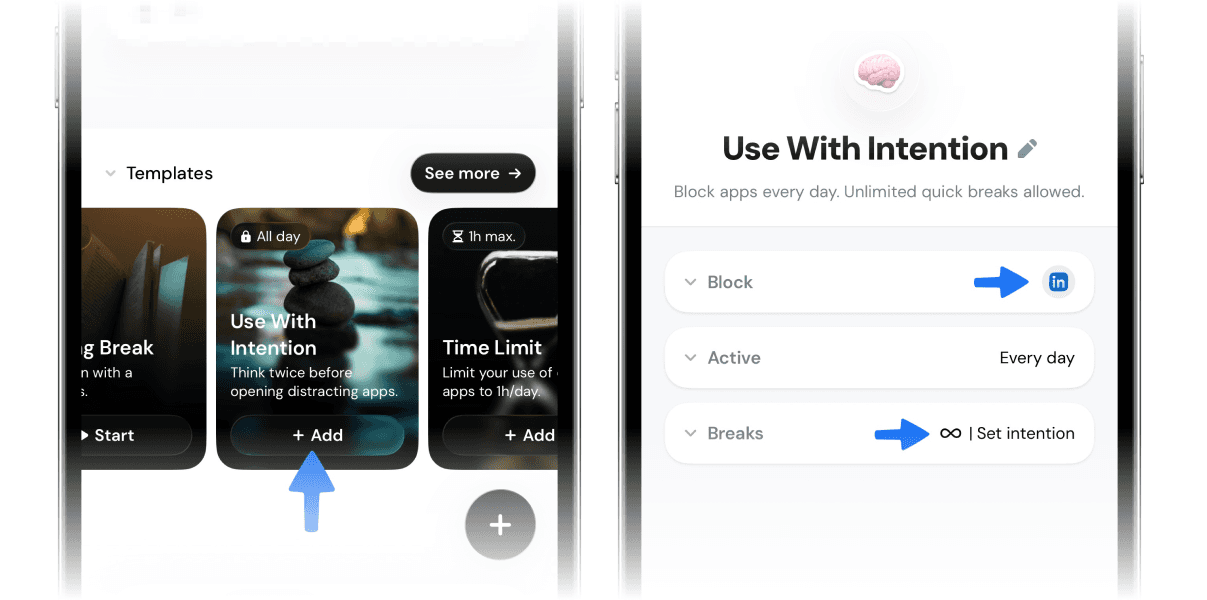

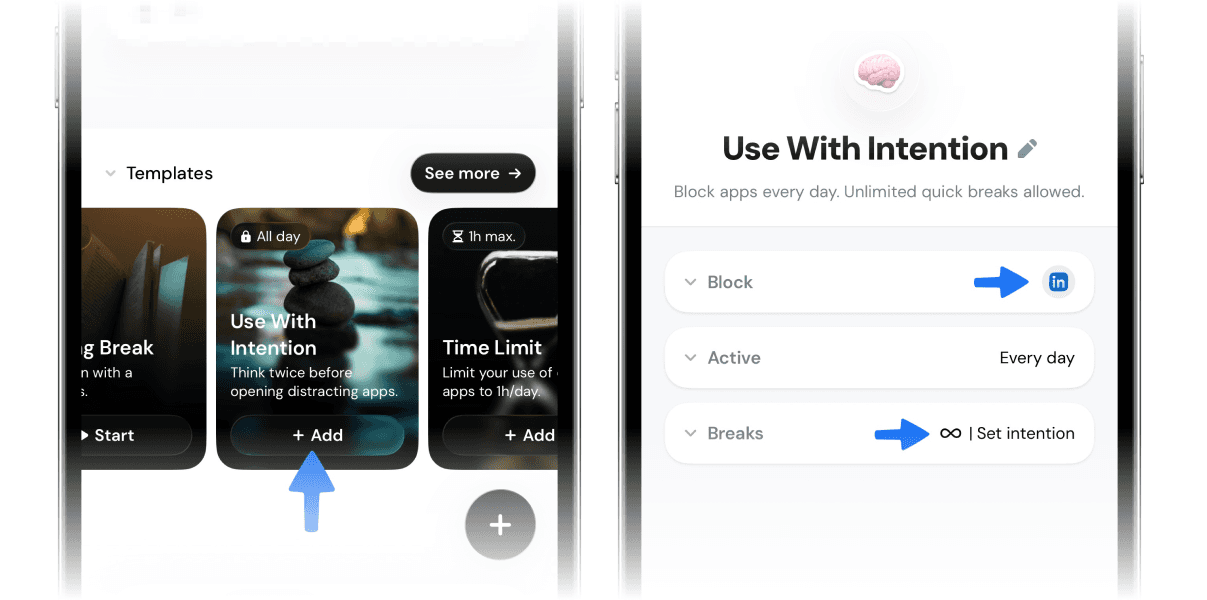

But you can also install the Jomo app, available for free on iPhone, iPad and Mac, to limit your LinkedIn consumption.

With Jomo, the goal isn’t to ban phone use altogether, but to use it more intentionally and mindfully. To stay in control—and not become a modern slave to that little device in your pocket.

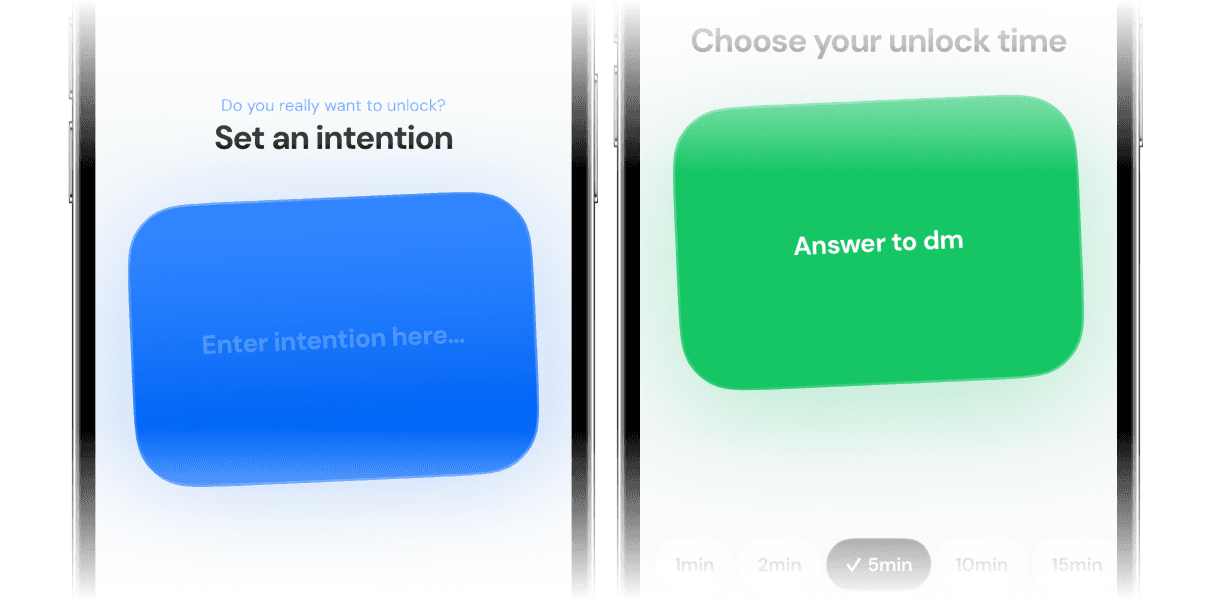

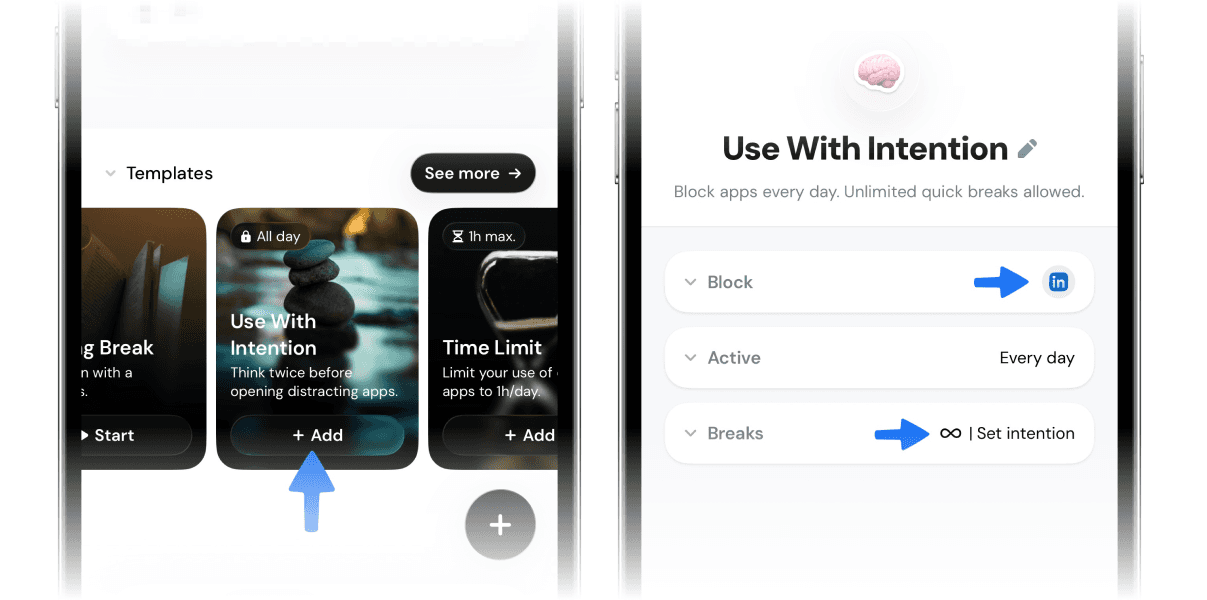

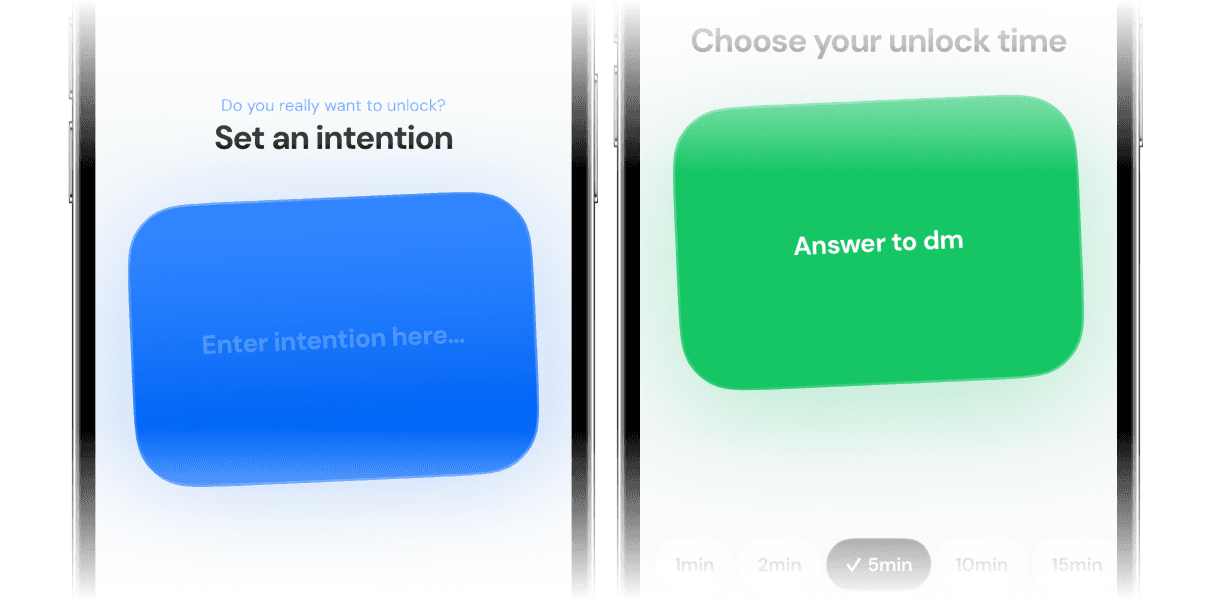

One of our favorite features in Jomo is a rule called “Use With Intention”, and it works incredibly well. The idea is simple: by default, your distracting apps are blocked. To use them, you’ll need to ask Jomo for permission. You’ll be prompted to explain why you want to use the app—and for how long.

It’s a powerful way to create distance without frustration, and to regulate your screen time without going cold turkey.

Here’s how to get started:

Go to the “Rules” tab

Scroll down to the “Templates” section and tap “Use With Intention”

Add the apps you want to block, and you’re all set!

The Dark Side

The irresistible need for social comparison can lead to compulsive behavior.

A distraction

That need—paired with infinite scroll—makes for a powerful time trap. The classic “just one minute” often becomes 20 or 30. Time you instantly regret. It’s hard to stop scrolling.

This is the intermittent reward principle, like a slot machine: even if only 1 in 10 posts interests us or sparks emotion, it’s the anticipation that keeps us hooked.

LinkedIn has become a quick and easy distraction: instead of focusing on your tasks, you check what others are up to. Low effort + comparison = a winning combo for the brain. And of course, once you’re on the platform, LinkedIn wants to keep you there. Proof: any external link in a post automatically reduces its reach (yes, it’s annoying for me too). Every notification, like, or profile view gives you a little dopamine hit. Which trains your brain to repeat the behavior: “Let’s check LinkedIn to see if there’s something new.”

Lower self-esteem and anxiety

It goes further than that. Habitually checking LinkedIn can intensify that nagging pressure of “Am I enough?”—a byproduct of repeated upward comparisons.

It’s the social network of winning. Every session, you’re bombarded with images of success and achievement. Watching from the sidelines can cause stress and anxiety—especially when it makes us feel uncertain. But comparison is also a defense mechanism against uncertainty—particularly when we’re feeling vulnerable. So it becomes a vicious cycle 🔄 …The more we compare, the more uncertain we feel. The more uncertain we are, the more we compare.

LinkedIn is a distorted mirror. We base our judgments on incomplete information. We take a single fact and draw conclusions about an entire person—their success, their happiness—and then compare all that to ourselves.

The truth is usually much more nuanced. The trap, like on all social platforms, is that we compare our inner world—our flaws—to the outer image others choose to show. This gap deepens the feeling of uncertainty. Social comparison also pushes people to self-promote on LinkedIn. And the platform becomes a masquerade.

The Great Theatre

American sociologist Erving Goffman came up with the theory of self-presentation—the strategies we use to shape how others see us. It’s all about making a good impression.

According to him, the social world is a stage, structured by norms, values, and desirable goals. We unconsciously view life as a performance, where we’re constantly playing a role. It’s all about presenting yourself as respectable and trustworthy. LinkedIn is no exception. Everyone plays their part—creators and consumers alike. As a consumer, we only interact with what we’re comfortable letting others (boss, friends, whoever) see. So we don’t always engage with what truly interests us. It’s the quest for social validation: approval and recognition from others becomes the goal.

As a creator, I really struggled at first. My early posts on LinkedIn were a major source of stress. To be honest, I was scared of looking like an idiot. More generally, that’s the issue with LinkedIn: out of fear of ridicule or backlash, people often share content that’s bland, flawless, and sometimes uninteresting.

Every user, wanting to keep a polished image, presents themselves a certain way. This uniformity hides the diversity of real experiences—making comparisons and inspirations less authentic, and therefore less valuable. The true essence of our stories and thoughts remains backstage. That’s why I appreciate the build in public trend—and I plan to do more of it.

Epictetus and Yesterday’s Self

Repetitive comparison and the hunt for validation can sometimes be motivating—but often, they’re a detour. We highlight what we lack, instead of building on what we have. And that makes us lose sight of what truly matters. The Stoic philosopher Epictetus once said:

“The greatness of the soul lies not in being superior to others, but in being superior to your former self.”

Yes, I know—it sounds a bit like a cheap motivational quote. But I truly believe it can inspire us. It’s an invitation to focus on our own progress. Even if the grass seems greener elsewhere, let’s tend to our own lawn.

On LinkedIn, that mindset becomes especially crucial. The platform constantly invites us to measure our journey against others—without context, without background, without considering the effort involved. We might find ourselves up against a level 80 Pokémon while we’re still at level 5. And we forget to put that duel into perspective. If we must compare, let’s at least do it thoughtfully—not impulsively. That’s why I’ve added friction to my LinkedIn use—because I know how the platform can make me feel.

The Trick

Even before I started writing content on LinkedIn, I was already spending a lot of time there. It kept growing. A few months ago, I installed the News Feed Eradicator extension—and I never looked back. Basically, it replaces your news feed with an inspirational quote.

I use it 95% of the time—even when I want to post or reply to messages. It lets me do what I came for without falling into the infinite scroll trap. It’s also a helpful reminder—“oh right, I don’t even know why I opened this”—when I land on LinkedIn out of habit. Once or twice a day, I’ll intentionally disable the extension for a few minutes to check in on what’s happening in my network—trying to stay an active, intentional user.

But you can also install the Jomo app, available for free on iPhone, iPad and Mac, to limit your LinkedIn consumption.

With Jomo, the goal isn’t to ban phone use altogether, but to use it more intentionally and mindfully. To stay in control—and not become a modern slave to that little device in your pocket.

One of our favorite features in Jomo is a rule called “Use With Intention”, and it works incredibly well. The idea is simple: by default, your distracting apps are blocked. To use them, you’ll need to ask Jomo for permission. You’ll be prompted to explain why you want to use the app—and for how long.

It’s a powerful way to create distance without frustration, and to regulate your screen time without going cold turkey.

Here’s how to get started:

Go to the “Rules” tab

Scroll down to the “Templates” section and tap “Use With Intention”

Add the apps you want to block, and you’re all set!

The Dark Side

The irresistible need for social comparison can lead to compulsive behavior.

A distraction

That need—paired with infinite scroll—makes for a powerful time trap. The classic “just one minute” often becomes 20 or 30. Time you instantly regret. It’s hard to stop scrolling.

This is the intermittent reward principle, like a slot machine: even if only 1 in 10 posts interests us or sparks emotion, it’s the anticipation that keeps us hooked.

LinkedIn has become a quick and easy distraction: instead of focusing on your tasks, you check what others are up to. Low effort + comparison = a winning combo for the brain. And of course, once you’re on the platform, LinkedIn wants to keep you there. Proof: any external link in a post automatically reduces its reach (yes, it’s annoying for me too). Every notification, like, or profile view gives you a little dopamine hit. Which trains your brain to repeat the behavior: “Let’s check LinkedIn to see if there’s something new.”

Lower self-esteem and anxiety

It goes further than that. Habitually checking LinkedIn can intensify that nagging pressure of “Am I enough?”—a byproduct of repeated upward comparisons.

It’s the social network of winning. Every session, you’re bombarded with images of success and achievement. Watching from the sidelines can cause stress and anxiety—especially when it makes us feel uncertain. But comparison is also a defense mechanism against uncertainty—particularly when we’re feeling vulnerable. So it becomes a vicious cycle 🔄 …The more we compare, the more uncertain we feel. The more uncertain we are, the more we compare.

LinkedIn is a distorted mirror. We base our judgments on incomplete information. We take a single fact and draw conclusions about an entire person—their success, their happiness—and then compare all that to ourselves.

The truth is usually much more nuanced. The trap, like on all social platforms, is that we compare our inner world—our flaws—to the outer image others choose to show. This gap deepens the feeling of uncertainty. Social comparison also pushes people to self-promote on LinkedIn. And the platform becomes a masquerade.

The Great Theatre

American sociologist Erving Goffman came up with the theory of self-presentation—the strategies we use to shape how others see us. It’s all about making a good impression.

According to him, the social world is a stage, structured by norms, values, and desirable goals. We unconsciously view life as a performance, where we’re constantly playing a role. It’s all about presenting yourself as respectable and trustworthy. LinkedIn is no exception. Everyone plays their part—creators and consumers alike. As a consumer, we only interact with what we’re comfortable letting others (boss, friends, whoever) see. So we don’t always engage with what truly interests us. It’s the quest for social validation: approval and recognition from others becomes the goal.

As a creator, I really struggled at first. My early posts on LinkedIn were a major source of stress. To be honest, I was scared of looking like an idiot. More generally, that’s the issue with LinkedIn: out of fear of ridicule or backlash, people often share content that’s bland, flawless, and sometimes uninteresting.

Every user, wanting to keep a polished image, presents themselves a certain way. This uniformity hides the diversity of real experiences—making comparisons and inspirations less authentic, and therefore less valuable. The true essence of our stories and thoughts remains backstage. That’s why I appreciate the build in public trend—and I plan to do more of it.

Epictetus and Yesterday’s Self

Repetitive comparison and the hunt for validation can sometimes be motivating—but often, they’re a detour. We highlight what we lack, instead of building on what we have. And that makes us lose sight of what truly matters. The Stoic philosopher Epictetus once said:

“The greatness of the soul lies not in being superior to others, but in being superior to your former self.”

Yes, I know—it sounds a bit like a cheap motivational quote. But I truly believe it can inspire us. It’s an invitation to focus on our own progress. Even if the grass seems greener elsewhere, let’s tend to our own lawn.

On LinkedIn, that mindset becomes especially crucial. The platform constantly invites us to measure our journey against others—without context, without background, without considering the effort involved. We might find ourselves up against a level 80 Pokémon while we’re still at level 5. And we forget to put that duel into perspective. If we must compare, let’s at least do it thoughtfully—not impulsively. That’s why I’ve added friction to my LinkedIn use—because I know how the platform can make me feel.

The Trick

Even before I started writing content on LinkedIn, I was already spending a lot of time there. It kept growing. A few months ago, I installed the News Feed Eradicator extension—and I never looked back. Basically, it replaces your news feed with an inspirational quote.

I use it 95% of the time—even when I want to post or reply to messages. It lets me do what I came for without falling into the infinite scroll trap. It’s also a helpful reminder—“oh right, I don’t even know why I opened this”—when I land on LinkedIn out of habit. Once or twice a day, I’ll intentionally disable the extension for a few minutes to check in on what’s happening in my network—trying to stay an active, intentional user.

But you can also install the Jomo app, available for free on iPhone, iPad and Mac, to limit your LinkedIn consumption.

With Jomo, the goal isn’t to ban phone use altogether, but to use it more intentionally and mindfully. To stay in control—and not become a modern slave to that little device in your pocket.

One of our favorite features in Jomo is a rule called “Use With Intention”, and it works incredibly well. The idea is simple: by default, your distracting apps are blocked. To use them, you’ll need to ask Jomo for permission. You’ll be prompted to explain why you want to use the app—and for how long.

It’s a powerful way to create distance without frustration, and to regulate your screen time without going cold turkey.

Here’s how to get started:

Go to the “Rules” tab

Scroll down to the “Templates” section and tap “Use With Intention”

Add the apps you want to block, and you’re all set!

Credits

This article is a revised version of Edition #30 of the Screenbreak newsletter created by Julien Rousset. With his permission, we're sharing this high-quality content with you today! So many thanks to Julien. 😌

Photographies by Unsplash, Dall-e, ScreenBreak and the Internet.

[1] Cherry - How Social Comparison Theory Influences Our Views on Ourselves, Very Well Mind, 2024.

[2] Wignall - 3 Psychological Reasons You Always Compare Yourself to Others, Nick Wignall, 2022.

[3] Arte - Dopamine, Linkedin.

[4] LinkedIn - Wikipedia.

[5] Haziq - Putting the best digital self forward in the age of Social Media, Medium, 2019.

[6] Friedmann - Se comparer aux autres, Sciences Humaines, 2011.

[7] Schwedel - LinkedIn Is Actually the Best Social Network for Self-Loathing, Slate, 2019.

[8] Social comparison theory - Wikipedia.

[9] Torrisi - FOMO: The Perils of Comparisons on Social Media, Gooding Welness Group, 2023.

Continue reading

Continue reading

The Joy Of Missing Out

Développé en Europe

Tous droits réservés à Jomo SAS, 2025

The Joy Of Missing Out

Développé en Europe

Tous droits réservés à Jomo SAS, 2025

The Joy Of Missing Out

Développé en Europe

Tous droits réservés à Jomo SAS, 2025